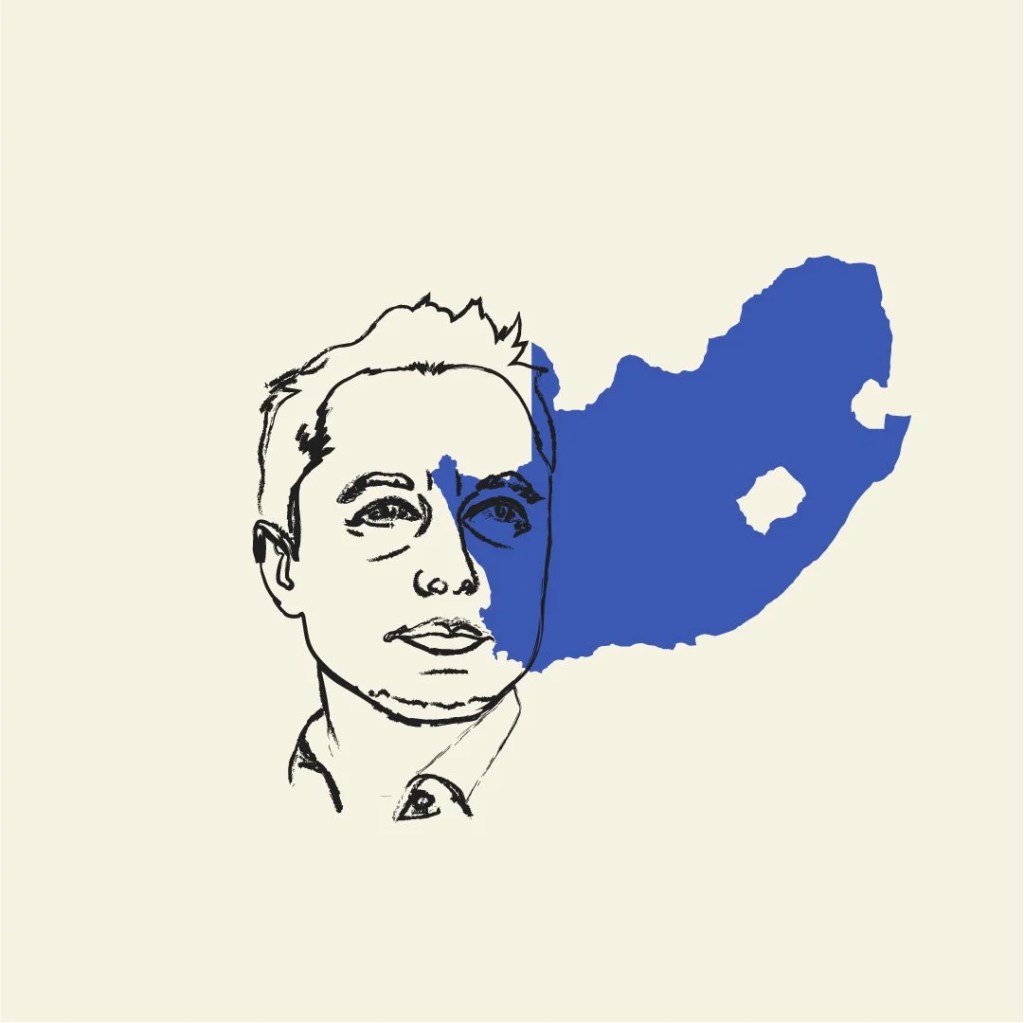

Elon Musk was born in South Africa during the apartheid era. Isaacson’s biography makes much of his early life: “As a kid growing up in South Africa, Elon knew pain & learned how to survive it.” But many of the book’s anecdotes of Elon’s time in South Africa are implausible.

Some things Isaacson recounts are extremely unlikely to have happened as he describes them.

In the 1980s, Isaacson claims, as a young teen, Musk and his brother once “had to wade through a pool of blood next to a dead person with a knife still sticking out of his brain” while getting off a train to go to an “anti-apartheid music concert”; at these concerts, “often, brawls would break out.”

But there were no explicit “anti-apartheid concerts” in South Africa in the ’80s. The apartheid government strictly censored music, and bands that played songs with lyrics perceived to criticize apartheid — or even bands with members of different races — were regularly harassed and arrested.

“I cannot believe the ‘knife in the head’ story,” Charles Leonard, a DJ and journalist who attended many gigs in apartheid-era Johannesburg, told me. “The concerts I attended were always peaceful.”

“The ‘wading through blood’ is invented, I’m sure,” Shaun de Waal, another Johannesburg journalist who covered 1980s South African society, said.

By the late 1980s, crime in South Africa had increased significantly, and by 199,1 the country had one of the highest murder rates of any in the world on a per capita basis. But violent crime was far rarer in the heavily policed areas around the Johannesburg railway stations and in the white-only neighborhoods where Musk grew up.

The book claims repeatedly that taking trains in South Africa was a terrifying experience and notes that Musk, who “developed a reputation for being the most fearless,” took them anyway: a train trip from the south coast to Johannesburg was “dangerous,” and on commuter lines, “sometimes a gang would board the train to hunt down rivals, rampaging through the cars shooting machine guns.”

Christopher Van, a South African train buff who helps organize a yearly celebration of the country’s railway history, took trains constantly throughout the ’80s and doesn’t remember them as dangerous at all: they were “fantastic,” he said. (All trains in South Africa were segregated by race through 1988.)

To the South Africans I spoke to, the gangs-on-trains story sounded like an infamous episode Musk might have read about: a 1990 massacre of black South Africans on a Johannesburg train bound for a black suburb. Whatever Musk may have experienced on trains, he had left South Africa by then.

Most everything Isaacson recounts about a 1980s white South African childhood struck the South Africans I spoke to as grossly exaggerated, warped beyond the point of recognition. Under apartheid, most white South African schoolchildren had to attend a wilderness camp called veldskool.

In “Elon Musk”, Musk describes veldskool as a “paramilitary Lord of the Flies” in which kids were allowed, and sometimes divided into two groups and encouraged, to fight each other over small rations of food and water. Every few years, Isaacson writes, one of the kids would die at the camps, and counselors told kids these grisly stories as warnings. But nobody with whom I spoke remembered hearing about deaths at veldskool.

Veldskool was all about discipline, designed to prepare boys to join the military, and “fighting was discouraged,” de Waal said. (For decades under apartheid, military service was mandatory for all young white men to battle Communist-aligned fighters in nearby countries and black South African liberation fighters who’d gone to those countries to train.)

My partner, a white South African born in 1970, participated in one of the wilderness camps and remembers a single incident of violence: a group of boys pinned down a Jewish child and drew a swastika on his forehead with a Sharpie.

That memory illuminates the core obfuscation that underpins Musk’s depiction of his South African upbringing in Isaacson’s book: that there was no prejudice.

“South Africa in the 1980s was a violent place, with machine-gun attacks and knife killings common,” Isaacson writes.

When recounting his first night in Montreal after leaving South Africa, Musk tells Isaacson that he slept on his backpack at a youth hostel because in South Africa, “people will just rob and kill you.”

But neither he nor Musk offers context for the tremendous violence he describes; it’s a mysterious mist of unknown origin.

No black South Africans appear in his biography, and while the word apartheid is mentioned, it is not defined as an explicitly Christian white-supremacist regime.

Search for “race” in Elon Musk, and you’ll find only one mention of race relations: a friend admiring that the adult Musk “has no biases about gay or trans or race.”

The absence of racial discrimination is the thing many South Africans find most unbelievable about Musk’s tale. Prejudice and racism were inescapable in 1980s South Africa. Your race was indicated in the digits of your national ID card. Schools were segregated. Black South Africans could not walk in white urban neighborhoods without a “pass” signed by a white employer.

The wilderness camps, for example, fed on concern about the dangers that “terrorists” — as the government called black-liberation fighters — posed to white children.

They also stressed general threats posed by Western liberalism — the culture that had generated rock music and free love but had also helped tear down Jim Crow in America.

Danie Marais, a poet, told me that he remembers an instructor at his camp playing Queen’s “Bicycle Race” backwards “and telling us we could hear the band singing, ‘Marijuana, smoke it now.’”

For even the most apolitical white South African child, racial politics was everywhere.

In a 2004 essay, Marais wrote about his childhood memories — and how disturbed he always feels when he recalls that they happened under apartheid:

“It seems unlikely, almost perverse, that one’s own personal experiences of beauty and innocence could have happened in such a time and place.”

Even as Isaacson depicts South Africa as a warped environment that distinctively molded its young people, he does not dwell on the nature of the pressures they were under. It’s a terrible pity, because most self-aware or honest South Africans of Musk’s age recognize that apartheid’s influences on them endure well into their 50s.

And a real investigation into how this real place — as opposed to a self-serving memory castle — made Musk who he is would have been fascinating.